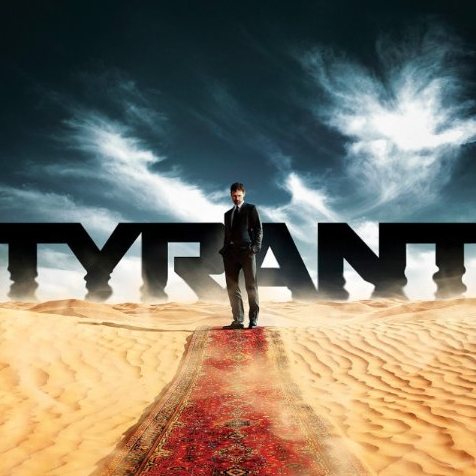

Jamal Al Fayeed (left) greets his brother, Barry, upon his return to Abbudin. Barry’s family watches cluelessly.

I didn’t expect to like the new FX drama Tyrant.

I anticipated an unrealistic plot; stereotyped characters and cultures; and a surfeit of Hollywood preachiness.

But after watching the first four episodes, I think the show is … not horrible. Not great – at least not yet – but worth monitoring to see where the writers go in its premiere season.

It seems that someone on Team Tyrant actually has a cursory knowledge of Middle Eastern history and pathology.

The plot centers on Bassam “Barry” Al Fayeed (Adam Rayner), a California pediatrician who returns home – a fictitious Middle Eastern nation called Abbudin – following two decades of self-imposed exile.

Ostensibly, Barry takes his wife and two children there to attend his nephew’s wedding. But Barry isn’t particularly festive about it. The second son of Abbudin’s dictator, he’s spent his adult life hiding from his father’s legacy. So it’s never clear why this nephew’s wedding would draw him back – or if he’d even met the kid.

Barry’s time away must have been lonely, because he doesn’t seem to have clued in his American wife, Molly (Jennifer Finigan). She thinks the trip is an opportunity for him to reconnect with his family and work through whatever has been eating him for 20 years. She has no idea.

The setup is obviously modeled on the biography of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, a London ophthalmologist called home in 1994 to succeed his father, brutal dictator Hafez al-Assad, following death of his older brother. Moreover, Bashar’s real father and Barry’s fictional dad both crushed revolts decades earlier with massacres lead by the younger men’s uncles.

The parallels are timely because Syria has descended into civil war and chaos in the last couple years. Bashar al-Assad remains in office, ruling over the capital and a few areas where his ethnic group dominates, but he’s fighting – probably literally – for his life.

Barry would like to see a better, more peaceful scenario in Abbudin. When his father dies at the end of the pilot, he decides to stick around and counsel the heir apparent, his mercurial older brother Jamal (Ashraf Barhom) – “mercurial” being a euphemism for violent and mentally unstable.

Barry quickly finds himself in no man’s land, nudging Jamal to liberalize the regime in opposition to the aforementioned uncle, iron-fisted Gen. Tariq Al Fayeed (Raad Rawi), who wants to crack down hard on any dissent. Tariq thinks hanging people the public square is the most effective way of shaping public opinion.

Raging Against Impotence

Midway through the pilot, Jamal is bitten in the groin and rendered impotent, at least temporarily. (Don’t feel badly for him; he was committing his third sexual assault in the pilot’s first 40 minutes when this went down.)

Jamal’s condition represents the pathology of impotence that has plagued the Arab world since at least World War I. Fed by a toxic mix of religion, colonialism and military defeat, it underpins the explosive violence and rampant misogyny in the region. The compulsion to rage against impotence has sabotaged political decision-making over and over. As Israeli diplomat Abba Eban put it in 1973: “The Arabs never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity.” The frustration also has reduced Arab society to oppressing the only people it can, its own women.

For a character such as Jamal, who’s already nuts, adding impotence on top of Daddy issues, poor self-esteem and the pressures of leadership makes a viewer wonder just when he’ll snap.

Tyrant isn’t subtle about demonstrating some of the links between impotence and misogyny.

It has twisted the knife a little further by casting an Israeli actress, Moran Atias, as Jamal’s beautiful, manipulative wife, Leila. That she returns to his bed just when he can’t perform and tries to become the Lady MacBeth of his nascent presidency further undermines Jamal’s confidence. Things will only get worse when Jamal discovers that Leila and Barry hooked up in their teenage years.

In addition, the chain of events that led to Jamal’s impotence was set in motion by the humiliated husband of a woman Jamal raped, and carried out by the victim herself when Jamal came back for more.

Yet Tyrant illustrates that the issue goes well behind Jamal. In Episode 4, an unemployed man is treated coldly by his wife, in front of their sons, for not being enough of a provider. He turns the resulting sense of impotence against the Al Fayeeds by self-immolating in a public square.

Before it even premiered, Tyrant drew criticism for filming in Israel and casting a number of non-Arab actors. Beyond Atias, there is Rayner himself, the product of an American mother and British father. The pilot implies that his Western looks come from a cold, English mother, who hasn’t appeared since.

The cast is comprised mostly of unknowns, which is why I haven’t been noting their past credits. One might recognize Atias from her earlier modeling career or Israeli-Arab Barhom from a few bad guy roles – he’s one of those “oh, that guy” actors – but that’s about it. The only exceptions are Justin Kirk (Animal Practice, Weeds) as American diplomat John Tucker and Jordana Spiro (My Boys, The Mob Doctor) as his wife, Dana, who – like Barry and Jamal’s mother – hasn’t been seen since the pilot.

It’s a pretty show. The close-up settings look realistic, even if the computer-enhanced palace settings and cityscapes look more like Oz than Dubai.

There is a lot of violence but surprisingly little gore. The dead simply fall to the ground. The character who burns himself alive considerately drapes a flag over himself before lighting up, and a hanging is unrealistically gentle.

Looking Ahead

Tyrant has a couple of challenges going forward.

With the exceptions of Barry, Jamal and Barry’s journalist friend Fauzi Nadal (Fares Fares), there is little depth to the characters, especially the women. Barry’s wife, Molly, so far has advanced only from clueless to naive – hardly what you’d expect from a woman who supposedly was, like her husband, a doctor back in California. Leila, for all her potential, has yet to evolve beyond anger and scheming. The kids are, for the most part, obnoxious and self-absorbed.

The writers also must break some new ground. The palace intrigue to influence Jamal, with Barry on one side and Leila and Tariq on the other, will get old quickly. (It’s hard to believe Tariq hasn’t had Barry whacked already.)

The writers also will have to come up with an original path for Abuddin. There aren’t any real-life examples of Arab dictators liberalizing while holding onto power. The show already has referenced Muammar al-Gaddafi’s ugly demise in Libya; Assad is fighting for his life in Syria. So even as the rebellion gains steam on Tyrant, it’s hard to see how the writers can proceed without killing off half of the characters – the Al Fayeeds or their opponents. The former would undercut the very premise of the show; that latter would leave little more than Dynasty: Arabia.

###

Stuart J. Robinson, a college friend of the TV Tyrant, is a writer, editor, media-relations practitioner and social-media guy in Phoenix.